diasporic lag in memory-making

“Rising and falling in relation to a shifting world, diaspora moments transform the self or group in question into an intermediary between two reified centers of power...thereby generating new knowledge and agendas.”

- Shelly Chan, “The Case for Diaspora,” 2015

I. introduction

In the winter of 2022-23, I used $3000 of Stanford’s grant money to cosplay as an American sociologist. I designed a survey based off Phinney 1992’s Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure, assigned value points to the responses of my 2,000 Chinese American subjects, and coded those responses in R to generate some bar charts and scatterplots. Those visuals were the only pops of color in my 140-page undergraduate thesis, Diasporic Lag in Memory-Making, a fever dream of a project that might’ve once been my ticket into academia.

I did not enter academia. I do, however, enjoy a career talking to people, which was the substance of my thesis’ other (much more enjoyable) empirical chapter. While R spat out p-values from chi-square tests, I interviewed twenty-two Chinese Americans about why they might’ve been taught to hate Japan. I recorded those interviews on Zoom, plugged the audio files into a seven-day free trial of a transcription software, then ran the PDF’s through a good old ctrl+F to determine keyword frequency. As it turns out, the best things in life are free.

My research question: Why, for all my life, had I grown up hearing about Japanese war crimes in the Sino-Japanese War? Why, when I was six, had I stood up in my history class to declare that the U.S.’ nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been not only strategically necessary but deserved?

It’s ironic that one of my very first personal memories overlapped with one of the most well-known state-sanctioned memories of modern history: Japan’s genocidal campaign during World War II.* It angered me that more people in the U.S. didn’t know this history—that my teacher and classmates seemed outraged by my proclamation—even as my fellow Chinese American students nodded in agreement or held their silence. Still more perplexing was witnessing the reactions of my mainland Chinese friends. During my year in Shenzhen (2021, two years before I wrote my thesis), I realized that most of them weren’t filled with the reactive, righteous rage that had animated me since childhood. Was it possible that we—diasporic Chinese, Chinese Americans, Chinese immigrants—were somehow closer to the original wound of genocide, despite our spatial and temporal distance from China?

We were required to input keywords into Stanford’s database before we submitted our theses. My keywords: reparations, genocide, collective memory, diaspora, imperialism. Back then, I couldn’t figure out a way to fit the-relationship-between-selfhood-and-state into one word, but that is ultimately the core of my thesis. I think it might be the core of all my work, particularly as certain illusions of state power shatter and others take their place.

*Just because I’m calling it state-sanctioned doesn’t mean I’m denying it. State-sanctioned narratives and real historical traumas can and do co-exist.

II. terminology & a little bit of history

Shelly Chan defines diaspora not as a spatial boundary or demographic marker, but as a process of creation. In her words, diaspora is an accumulation of “moments in which reconnections to a putative homeland take place” (Chan 2015, 109). These “diaspora moments,” which might include making Chinese food, scrolling through Xiaohongshu, or talking to Chinese friends, create a unique understanding of self that may be reinforced by repeated actions or altered by different ones.

San Francisco Chinatown, home to one of the most famous Chinese diasporas in the world, was the site of one such creative process. During World War II, an unprecedented wave of diasporic nationalism swept through the country. Chinese Americans organized fundraisers in over 2,000 U.S. cities to support the allied war efforts of China and the U.S. The biggest of these events, hosted in San Francisco Chinatown in 1940, raised upwards of $80,000: enough to purchase a squadron of Boeing P-26 fighter planes and to send aid to relief units across China. Chinese American pilots such as Hazel Ying Lee, John “Buffalo” Huang, and Arthur Chin joined the Nationalist Air Force of China, while Chinese American artists such as Dong Kingman created paintings to persuade the U.S. government to lend aid. And countless Chinese American laborers jumped to fill the vacancies left by white workers-turned-soldiers. Wrote Kenneth Bechtel, president of Marinship,

“We have learned that these Chinese Americans are among the finest workmen. They are skillful, reliable – and inspired with a double allegiance. They know that every blow they strike in building these ships is a blow of freedom for the land of their fathers as well as for the land of their homes.”

Chinese Americans took great pains to distance themselves from Japanese Americans, who were relocated en masse to concentration camps across the country. They also took great pains to denounce Japan, which had launched a colonialist project across the rest of Asia. But this was not entirely a matter of patriotism. Chinese Americans recognized the rare opportunity to raise their status in the eyes of American society. In 1940, the motto of New York City’s Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance read: “To Save China, To Save Ourselves.”

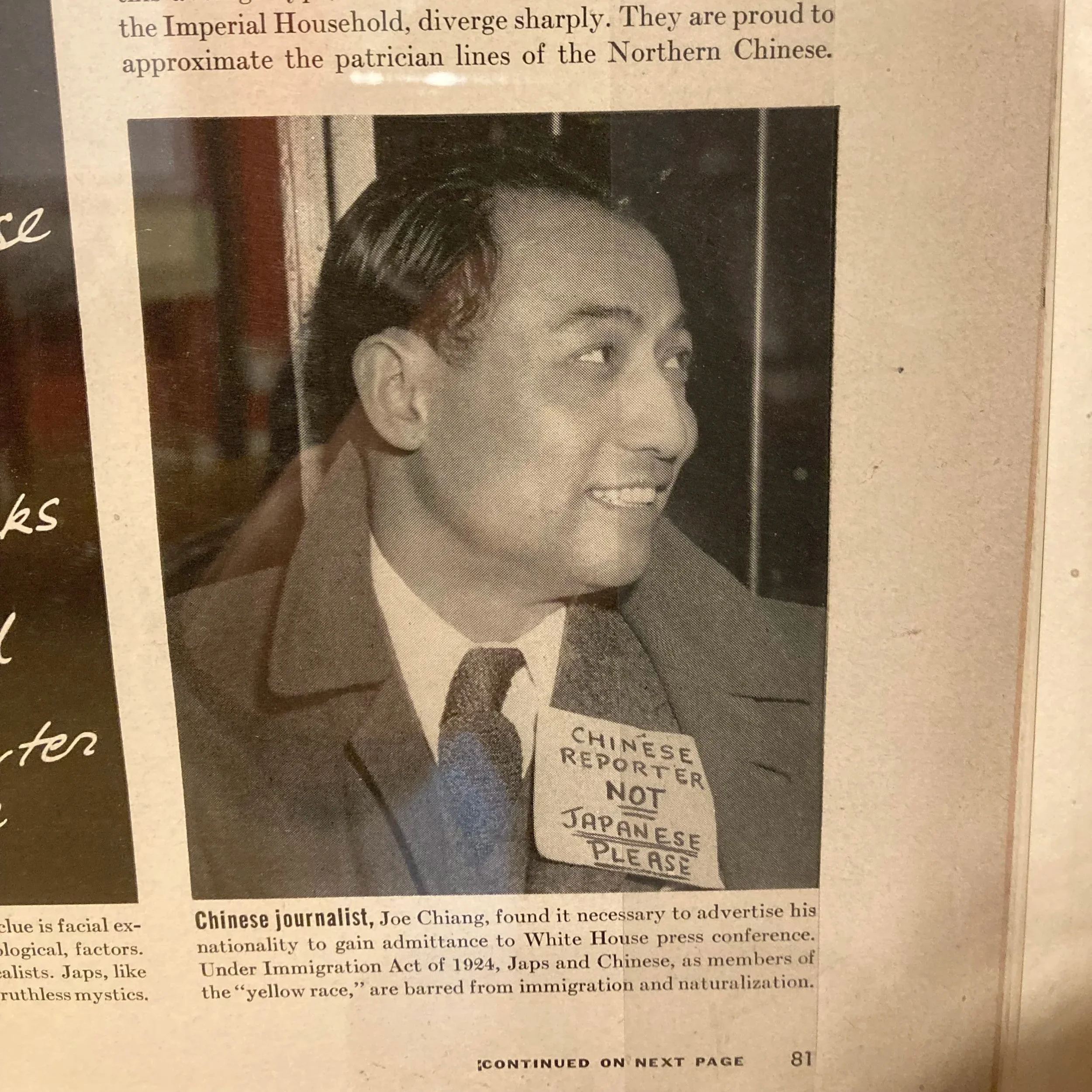

Figure 1: A photograph of Joe Chiang at the Japanese American Heritage Museum in Los Angeles. I have a lot of thoughts on museums as a site for/invitation of grief.

IIIa. more history

The Second Sino-Japanese War, known in China as the 抗日战争, began on July 7, 1937 and concluded on September 9, 1945. The Japanese government had long been pushing a colonial expansionist policy in Asia—nationalizing key industries, centralizing state power, establishing puppet governments in different countries. Meanwhile, China had fractured into warring factions after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, a situation worsened by a century of foreign colonization and warfare. The leader of the Guomintang (KMT), Chiang Kai-shek, focused his efforts on suppressing these warring factions while retreating westward across China, giving up key cities such as Beijing and Shanghai to the Japanese army. Despite their repeated appeals, the KMT would not receive any aid from the U.S. until 1941, when the Japanese army bombed Pearl Harbor.

By the war’s end in 1945, over 1.5 million Chinese soldiers were pronounced dead; over three to four million were declared missing. More than ten million Chinese citizens had been murdered by the Japanese army, and hundreds of millions more had been displaced. Frequently excluded from historical narrative are the 50,000 to 200,000 Chinese women who were abducted into sexual slavery, who (like other comfort women across Asia) have yet to see substantial reparations.

What happened after? Post-war transitional justice efforts in East Asia—both bilateral and international—were neglected, then forgotten, in the chaos of the Chinese civil war and the reshuffling of the post-WWII world order. Once the Chinese Communist Party ousted the Guomintang and consolidated power in China, Chairman Mao Zedong decided not to endanger his new regime in a world that had become decidedly anti-communist. Beijing displayed exceptional lenience toward Japanese war criminals in the decade following Sino-Japanese War: of the one thousand war criminals put on trial, only forty-five were imprisoned.

IIIb. even more history—histories—?

The entire third floor of the Museum of the Chinese Diaspora, located on the east side of central Beijing, is dedicated to the relief efforts of Chinese Americans during World War II. Unlike the other floors of the museum, these museum tags are printed only in Chinese. Handfuls of neon English letters shout from fundraising posters, magazine clippings, badges. BUY A BOWL OF RICE FOR CHINA! HANDS OFF CHINA! PLEASE: I AM CHINESE, NOT JAPANESE. (Read: Do not hurt me.) I snuck between tour groups, listening to guides praise the diasporic martyrs who had given up their lives for China, and I wanted to cry.

Had there ever been such a showdown between the forces of good and evil like in World War II? Will there ever be again? The alliance between the U.S. and China—their synchronous victimhood and victory—only happened that one time. It will probably never happen again. But when it did, it launched its diasporic subjects to stardom. As I stared at Hazel Ying Lee’s portrait through the glass, I thought, you are so cool. Everyone loves you.

And then, I realized that the time for the Chinese American hero was over. Has been over since China renounced capitalism in the 50’s and became the U.S.’s next top rival in the 60’s. What’s a diasporic girl to do, when she can’t martyr herself for her two countries at once? There are a handful of contemporary Chinese Americans who have continued to work with the trauma of war. The late historian Iris Chang, who wrote The Rape of Nanjing in 1997, garnered commercial success in the U.S. and China; many Chinese readers consider her post-publication suicide to be a casualty of the titular Rape of Nanjing. R.F. Kuang’s 2018 fantasy novel, The Poppy War, also took Japanese colonialism as inspiration. In an interview with Ifeoluwa Adeniyi, she called it a “revenge fantasy.”

My visit to the Museum of the Chinese Diaspora—which occurred in January 2026, nearly three years after the completion of my thesis—might be considered one of Chan’s “diaspora moments.” A moment of reconnection with state-sanctioned narratives about history and identity. In spaces like this, which are shaped by and exist in service of a single historical narrative, it’s easy to forget that there exists many interpretations of the Second Sino-Japanese War. That this history has been treated differently over the decades, massaged into a variety of stories to serve a variety of agendas.

Every nation needs a founding myth. During the 1950s and 60s, that myth was the CCP’s triumph over the KMT in the Chinese Civil War. The CCP cast both foreign and domestic conflict through the lens of class struggle: textbooks published during the 1950’s and 1960’s forefronted China’s peasant rebellions throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The lens of class struggle also informed the CCP’s interpretations of the Second Sino-Japanese War. In an attempt to separate the Japanese state from Japanese civilians, official narratives claimed that Japanese peasants and laborers were fellow victims of Japanese imperialism, who did not wish for war and did not deserve to be punished.

But the 1980’s saw the end of the Cold War and the introduction of a capitalist economy in China, which began to undermine the legitimacy of communism as a guiding ideology. Democracy movements erupted across the country, the most prominent being the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. Millions of urban residents, who had been sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, returned en masse to cities. The government needed to craft a new Chinese identity, and a new narrative around which this identity could be legitimated.

Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, the CCP began to introduce anti-Japanese rhetoric in textbooks and national narratives. This effort culminated in the 1991 Patriotic Education Campaign, during which the State Education Commission instructed schools to “integrate the teaching of patriotism and national condition with the education of love for socialism and the CCP.” Chinese policymakers protested the omission of the phrase “invasion of China” from Japanese textbooks, called for the removal of the head of the Japanese Ministry of Education, and boycotted summits in protest of Japanese leaders’ visits to shrines glorifying Japanese wartime heroes. Slowly, the rosy “victor’s narrative” of the Chinese civil war was replaced with a “victimization narrative.” China’s wartime humiliation began to serve as the rallying cry for a new anti-Western, anti-imperialist nationalism.

The new campaign caught on quickly. Far-right nationalist movements rose within the nascent Chinese internet, culminating in protests against the Japanese government. When President Jiang Zemin visited Japan in 1998, he was met with backlash from Chinese citizens, prompting him to cancel upcoming talks with Prime Minister Koizumi in 2002. Such anger could not even be placated by the Japanese government’s apologies. In 2013, after former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama issued a formal and personal apology for Japanese actions committed during the war, Chinese sentiments towards Japan plunged to an all-time low. According to the Pew Research Center, 8% of Chinese citizens believed that Japan had apologized enough in 2008, but only 3% of citizens believed the same by the end of 2013.

This anger isn’t uniform. In 2015, Jeremy Wallace and Jessica Chen Weiss identified variations in anti-Japanese protests across China. They found that the presence of a Patriotic Education Base—a site created by the government to memorialize wartime history—was a much likelier predictor for the occurrence of a protest than the city’s history of occupation by the Japanese army. Constructed memories, it seemed, were more volatile than inherited ones.

In 2018, Orna Naftali identified a second variation in anti-Japanese sentiment along China’s rural-urban divide. While all mainland Chinese youth retained a sense of injustice toward the war, those who received an education in a metropolis (e.g. Shanghai) and came from wealthier families offered more nuanced perspectives on the war. They were less likely to express anti-Japanese anger than those who were raised and educated in the countryside, attained lower levels of education, or who had family members who had attained lower levels of education.

The work of Wallace, Weiss, and Naftali was the first sign that my instincts might have some footing in reality. There seemed to be a propagandic lag across China: a delay in political narratives, or the material benefits of modernization, that resulted in higher levels of anti-Japanese anger among low-income rural communities. Could I also find this lag in diaspora?

IV. cosplaying sociologist, cosplaying anthropologist, cosplaying neutrality, hypotheses, variables, survey design, survey findings, interview findings. empirics?

Despite the inflammatory questions in my introduction, I had—and still have—little interest in comparing the scale of mainland and diasporic anger. The main body of my thesis is concerned with how memory is passed from motherland to diaspora, how trauma can be distorted, and how generational anger can be reawakened (or perpetuated) with no obvious political agenda.

Ironically, the hypothesis I cared most for was labeled H1b. It read: First-generation immigrant parents are spaceships. They crystallize the political narratives that were most salient in their childhoods, before carrying those narratives to the U.S. and bestowing them upon their second-generation children. Those who left China around the time of the Patriotic Education Campaign (the late 80’s and early 90’s) would maintain vehemently anti-Japanese beliefs in line with the rhetoric of the campaign. Their children would, too.

In an earlier draft of this post, I included and explained all of the p-values, t-tests, bar graphs, chi-square tests, OLS regressions, and s6dlfjl23 to prove not only my hypotheses, but also my credibility as a social scientist. Beta readers kindly informed me that the draft was unreadable.

Figure 2: But I’m trying so hard…

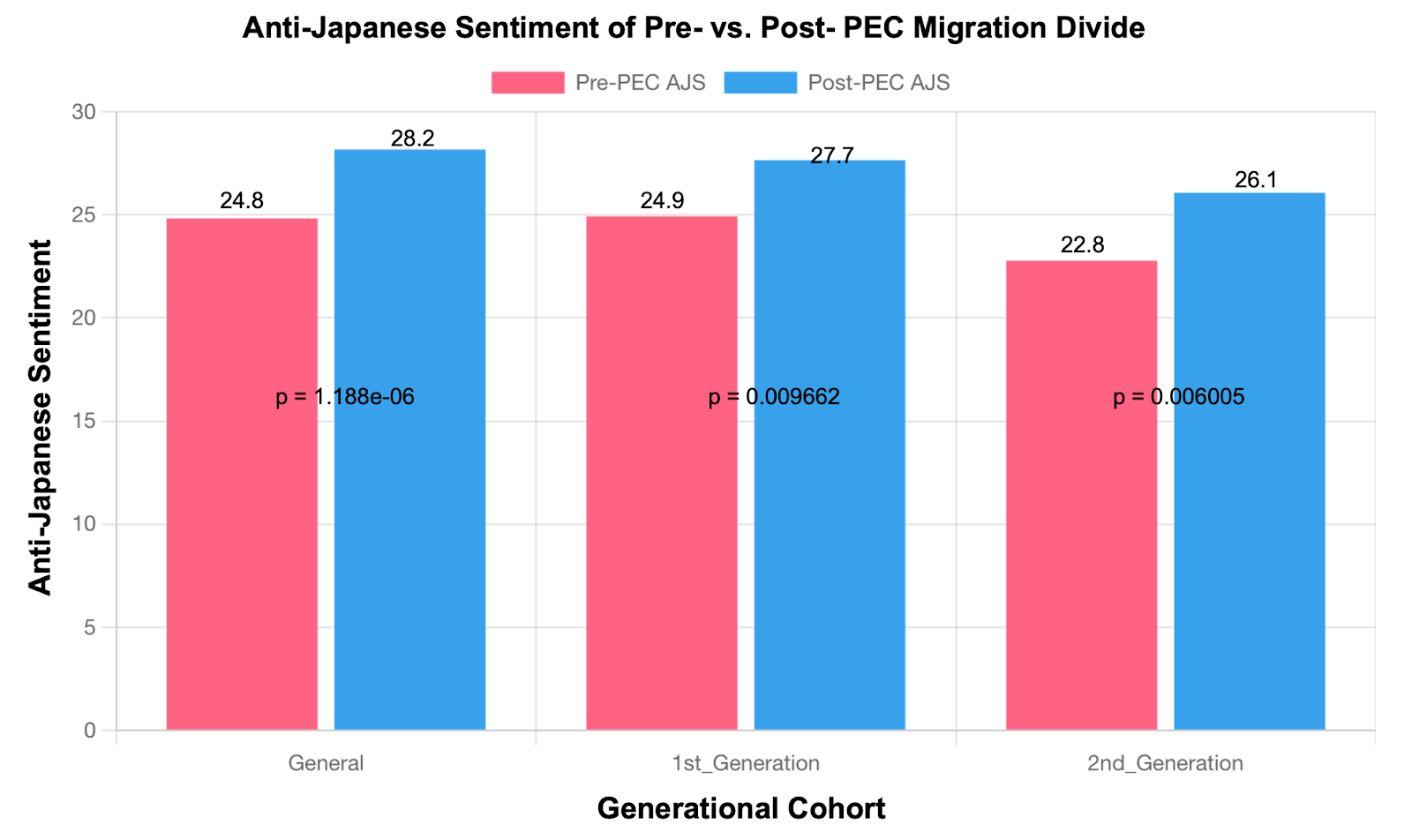

It was unbelievable how quickly I proved hypothesis H1B. The process took less than three months: designing a variable to measure Anti-Japanese sentiment (AJS) with survey questions based off the 2013 Pew Research Center study, hiring a survey company to send those questions to all the Chinese Americans they could find, then cleaning my data for analysis.

Three chi-square tests in, I found that anti-Japanese sentiment was notably higher among immigrants who had left China after the beginning of the Patriotic Education Campaign, as opposed to those who had left before. Six chi-square tests in, I found that this difference persisted (was in fact slightly more pronounced) among children whose parents had migrated before versus after the Patriotic Education Campaign. Twelve chi-square tests later, I found that respondents who had indicated their parents as the primary source of information about the war demonstrated the highest levels of anti-Japanese sentiment, but only if those parents had migrated after the beginning of the Patriotic Education Campaign. And one-hundred tests later, I could prove everything except causation: second-generation Chinese Americans were noticeably angrier at Japan if their parents were exposed to state-sponsored narratives about Japan, or if their parents came from regions with Patriotic Education Bases dedicated to commemorating the war.

Figure 3: A pop of color.

These state-sponsored narratives didn’t just come from textbooks and museums. Chinese war dramas, in which the CCP’s People’s Liberation Army is depicted as the primary hero against Japan, played a key role in shifting China’s national narrative about Japan during the Patriotic Education Campaign. Many of these dramas have since reached the U.S., continuing to circulate after their release and/or cancellation in the mainland. (California’s KTSF is one such port for these wandering ghosts.)

When I asked my interview subjects about their impressions of the war, many second-generation respondents used the language of war dramas—which they had consumed in childhood—to describe the Japanese army: “Less than human,” “dumb,” “ruthless,” “small.” The vast majority of them used language such as “antagonist,” “protagonist,” “bad guy,” and “good guy” to narrate the war, even when such language was not prompted by my questioning. Crucially, this language was not found in narrations of war offered by first-generation Chinese Americans, nor by second-generation interviewees who had no childhood exposure to war dramas.

Okay, I said. So, can you walk me through your thoughts on Japan? How might have they changed through childhood and adulthood?

The second-generation respondents’ stories followed similar arcs to mine, though I (the impartial interviewer) did not tell them this. Almost half of them instinctively identified with individuals of Japanese descent in childhood, before they became aware of their parents’ anti-Japanese sentiments. One elderly respondent, who had grown up before the concept of a pan-ethnic Asian American identity had taken root in the U.S., narrated their childhood playing with the kids of Japanese farmers in California’s strawberry farms.

Then, something changed. All but one of my second-generation respondents reported sensing anti-Japanese sentiments in their childhoods: negative impressions of Japan that would predate any factual understanding of the war itself. Half of my respondents were descended from family members who had fought in or had been displaced by the war, but only two reported learning of it directly from their grandparents. The others either learned from their parents’ secondhand accounts, or picked up the pieces from whispered conversations.

For those who learned of the war from their parents, anti-Japanese sentiment was often packaged as practical advice. One-third of the second-generation respondents reported hearing from their parents or grandparents that they should not associate with Japanese people, enjoy Japanese culture, or cheer for Japan in sports tournaments. All of them reported feelings of guilt when they did try to interact with Japanese people or culture.

Later, anti-Japanese sentiment was inflamed by and interpreted through respondents’ experiences with racism in the U.S. All of my second-generation respondents, and most of my first-generation respondents, reported feelings of outsidership or experiences with racism in the U.S., even if they grew up within a predominantly Chinese community. These experiences shaped their interpretation and justification of many things: first their anger toward Japanese genocide, then their doubt toward the media designed to villainize Japan. About a quarter of second-generation respondents drew upon the U.S.’ legacy of racism to understand the history of Japanese colonialism and to outline potential models for reparation. Some respondents also criticized the lack of understanding among liberatory thinkers in the U.S.

Respondent (shared with permission): “When I was in fifth grade, I was aware that people always thought of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans as being a model minority, since we have a high median income, we’re very educated, that sort of thing. And I was aggrieved by that, because I knew that we’re discriminated against. We have all this traumatic history. And World War II was just this really powerful piece of evidence in my mind. The U.S. never took the brunt of World War II like China did. I remember learning that W. E. B. DuBois was somewhat enamored by Japan’s idea of pan-Asianism. And he didn't realize that their Pan-Asianism was just colonialism, that Japan planned to wipe out other peoples. Even DuBois, who is so respected for his work on race here in the U.S., was so blind to Japan's rise, and that shows the general Western ignorance and complicity towards wartime Japan.”

Where can we go—who can we turn to—to affirm our anger? The answer is obvious. Almost all of my second-generation respondents reported seeking out mainland Chinese accounts of the war—war dramas, social media, news channels—in the absence of other resources. In my interviews with them, I witnessed their defensiveness over their Chinese heritage and the Chinese state, and struggles of various intensity to disambiguate the two. A quarter of the second-generation respondents stated that their outsidership in the U.S. led them to become more hesitant in criticizing China as a nation. This hesitancy increased when they left their families to go to college, or else felt more isolated from their Chinese communities.

First-generation respondents were, by and large, far less sentimental. Those who had spent their childhoods and adolescence in China displayed a heightened awareness of the propagandic nature of their educations, a skepticism that enabled them to hold more nuanced opinions of Japan.

One respondent who was born and raised in the U.S., but who spent their middle and high school education in Beijing, stated that their experiences living and studying in China disillusioned them with the Chinese state, leading them to adopt a more nuanced perspective on Japan. Due to their migration to China and back, they identified as neither first- nor second-generation Chinese American.

Respondent (shared with permission): “I felt very alienated by the U.S. when I was a child, so I kind of chose to align with like the Chinese nation-state. I was always proud of being Chinese...I wanted to have a stronger connection to my Chinese sense of heritage. I was reading tons of stuff about…Chinese [politicians and] history. [But] when I went back to China, I actually met Chinese people who were not all from the same background...and I became very anti-CCP for some time. I was even a little bit pro-U.S. for some time, which is weird, because when I was living in the U.S., I always hated the U.S. Now, as a college student, I don't like the U.S. I don't like China. I just care about people, and that's it. I’m distrustful of what both countries teach...neither teach the whole story about World War II, and the correct thing to do is to see the issues in both the U.S. and the Chinese narrative.”

By consequence of their upbringing in China, this participant, and most first-generation Chinese Americans, was subject to a greater diversity of narratives than were their second-generation counterparts, resulting in a separation of the Chinese nation-state (generally viewed negatively) from their Chinese heritage (generally viewed fondly).

Previous respondent, continued: “My political views flip-flopped when I was actually living in China. I think a lot of Chinese diaspora people do romanticize China. They think of it as this perfect place...until you actually go to live there and you actually start to learn about the nuances. After I moved to China, I definitely had a much stronger relationship with Chinese culture...but a more negative view of the [state].”

No longer did this participant feel the need to adhere to the Chinese nation-state to affirm their ethnic identity or to alleviate their feelings of outsidership in the U.S. They could afford to criticize China when it was no longer their primary access point to their Chinese identity. By living amidst Chinese citizens who held a variety of opinions on China—but whose voices they could not hear in the U.S.—they may have been encouraged to hold more critical opinions of their own.

Second-generation respondents seemed to know this, too. They expressed a longing to learn more, to move beyond understandings of state and self that are shaped by nostalgia or defensiveness. I dedicated the final portion of my interviews to my respondents’ hopes for the future: what they wanted to see from themselves, from China and Japan and the U.S., from the people around them. Perhaps my interviewee sample was too self-selecting—too inclined to self-reflection—for me to draw any conclusions about the state of diasporic anger, but I couldn’t help but feel hopeful. No matter how vehemently my respondents had denounced Japan in their childhoods, no matter how much they’d been taught to hate, they agreed that their anger would not lead to healing. Unanimously, they decided that they needed time to form their own opinions. Access to resources and teachers. And, most importantly, to maintain their curiosity in the face of great hurt.

V. conclusion: things to do at lightspeed

In the afternoon after my thesis defense, a student found me in the bathroom of Encina Hall. I just wanted to say that I’m also Chinese American, and I loved your thesis, she said. Love—an unusual response to academic research. I just kept thinking, she continued, is this play about us? A Euphoria meme—an even more unusual response to academic research. I almost laughed. I almost wept. I felt immense relief.

As much as I tried to play the role of the impartial researcher, my thesis had become a diaspora moment of its own. It had bid me to reconsider my own place in painful family histories, the rippling effects of unresolved traumas, the ambiguity of my relationships with two powerful countries. In the weeks after I submitted my thesis, I was tempted to follow up with my interviewees. I imagined taking them to lunch and asking, Hey, now that we’re no longer interviewee and interviewer, what do you think of it all? How do we navigate this confusing tangle of pain and state-sanctioned trauma? Can we form our own relationships with our homelands, or are we doomed to yearn forever? That’s easy for me—I’m a lesbian—but what about the straight people of the diaspora?

There isn’t an obvious political agenda to diasporic anger. It just sits there, radiating like the heat of a raw wound, until it detonates. Or—maybe, it doesn’t have to. Sometimes, I imagine stripping the anger from my chest and laying it out to dry, like the orange peels on my Popo’s rooftop. I’d kneel down and sit in the pulp of my rage. I’d turn my face to the sky.

It’s a traitorous thought. It might be as traitorous as cracking a joke about martyrdom. We in the diaspora are expected to act in loyalty and submission. To be perpetually the learner and child. (For the record, I don’t mind being either—what I mind is the illusion that learners and children have no agency, or, worse, that they should have no agency.) But there is great mobilizing power within diaspora, and we can choose where to direct it. We can choose to engage with local politics, to fight for communities beyond our own, to refuse narratives that glorify us at the cost of others. These ideas aren’t mine. They’re common critiques of insular Asian American and Asian immigrant communities.

There is no act of becoming that doesn’t preclude yearning. We are all seeking surrender to something greater and truer, a condition that is not unique to diaspora. In my time in Beijing, I haven’t met a single Chinese person who is certain of their place in contemporary Chinese society. Everyone wishes for something that they lost: a village plowed over for an abandoned construction project. The 90s punk/rock/alt scene of Beijing, which birthed legends like Cui Jian and Secondhand Rose, and which choked out of existence after COVID. The 2010s, that dawn of a global village that never came to be, before our brains fused with Meituan and Douyin and DeepSeek. We are all wanting for different homes and selves, which we see in fractured bits according to the information most available to us.

To overseas audiences, those sources of information are the state-sanctioned ones. But it is imperative for diasporic individuals to find and build diverse understandings of homeland, understandings capable of holding contradictions and critique. It’s an effort that takes a lot of time, an endeavor with many prerequisites: language fluency, familiarity with digital and physical ecosystems, comfort and belonging within subcultures. It’s also very rewarding.

I keep thinking about Chan, about those diaspora moments “in which reconnections to a putative homeland take place.” I would expand on that definition. Chan’s diaspora moments need not be re-connections, and the focus of those connections need not be the homeland. I have learned much about being Chinese from my fellow Chinese Americans, from people who do not claim any Chinese heritage, and from people engaged in political struggles similar to those within the Chinese diaspora or mainland. To be diasporic is to owe oneself to many things, and to fight for many things too. To cloister ourselves within a single cause, lineage, or identity—to look away from the struggles of "other" and "elsewhere"—is to deny what makes us diasporic in the first place.

In the first draft of my thesis, I wrote about the speed of light as a metaphor for diasporic lag. We never see a celestial body as it is in the moment, but as it was in lifetimes past, an image frozen across the cosmos. So we stand still, heads tilted up in deference, as we seek guidance from the light-echo of stars long gone. But that light need not be our only beacon: not when our feet have already carried us across so many seas, not when our hands have already built homes in inhospitable worlds. We, too, are the stars.

VI. acknowledgements

The title of my thesis, Diasporic Lag in Memory-Making, is credited to a great friend and mentor, the soon-to-be-Dr. Christine Xiong. Christine’s incisive humor and feedback made me love the work of research (not an easy feat), and you should all be following her journey with your eyes peeled.

Sharp Queener, Rachelle Rodriguez, and Gwen Phagnasy Le, who wrote their theses alongside me, helped me navigate the discomfort of shoving a square peg into a round circle (fitting deeply personal findings into academic writing). I was afraid of angering The Powers That Be, whether that be writing without a methodology, denouncing imperial and colonial practices within academia, or otherwise eschewing the conventions of American political science. But they were brave, and I hope to be too, particularly as I am now free(r) from Said Powers.

I am very indebted to Nikita Salunke, who taught me how to code in R after I slept through a semester of STATS60. I am also indebted to aforementioned beta readers, Simon Wu, Jessie Liu, Jessie Liu’s escargot, and Michelle Wang, who told me to save my 30-page draft for an academic conference. I am also also indebted to my advisors and mentors—Professors Aliya Saperstein, Erica Gould, Dongxian Jiang, Rama Mitter, Annie Nie, and Thomas Mullaney. And lastly, I am grateful for my interview subjects, whose willingness to examine themselves inspires me to this day.

Works Cited

This is an incomplete bibliography that includes only the sources I used in this article! For more sources, just hmu.

Adeniyi, Ifeoluwa. “Speculative World-Building as a Refracting Prism.” American Studies, Fall/Winter 2021, Vol. 60, no. 3/4, pp. 119-126

Chan, Shelly. “The Case for Diaspora: A Temporal Approach to the Chinese Experience.” The Journal of Asian Studies 74, no. 1 (2015): 107–28.

Chang, Gordon. Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad. May 2019. Mariner Books.

Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking: the Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. 1997. New York. BasicBooks.

Coble, Parks M. “China’s ‘New Remembering’ of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937-1945.” The China Quarterly, no. 190 (2007): 394–410.

Ding, Sheng. “Digital Diaspora and National Image Building: A New Perspective on Chinese Diaspora Study in the Age of China’s Rise.” Pacific Affairs 80, no. 4 (2007): 627–48.

He, Yinan. “Forty Years in Paradox: Post-Normalisation Sino-Japanese Relations.” China Perspectives, no. 4 (96) (2013): 7–16

He, Yinan. “Remembering and Forgetting the War: Elite Mythmaking, Mass Reaction, and Sino-Japanese Relations, 1950–2006.” History and Memory 19, no. 2 (2007): 43–74.https://doi.org/10.2979/his.2007.19.2.43.

Huang, Yifang. “Chinese Americans in San Francisco during World War II - FoundSF.” Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Chinese_Americans_in_San_Francisco_during_World_War_II.

Louie, Andrea. “Re-Territorializing Transnationalism: Chinese Americans and the Chinese Motherland.” American Ethnologist 27, no. 3 (2000): 645–69.

Mitter, Rama. China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism, 2020. Belknap Press

Naftali, Orna. “‘These War Dramas Are like Cartoons’: Education, Media Consumption, and Chinese Youth Attitudes Towards Japan.” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 113 (2018): 703.

Stokes, Bruce. Hostile Neighbors: China vs. Japan. Pew Research Center, September 2016. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2016/09/13/hostile-neighbors-china-vs-japan/

“‘Three Hundreds’ List of Patriotic Education- Government Portal of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China,” October 6, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20201006070705/http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/moe_364/moe_1172/moe_1202/tnull_20106.html.

Wallace, Jeremy L., and Jessica Chen Weiss. “The Political Geography of Nationalist Protest in China: Cities and the 2012 Anti-Japanese Protests.” The China Quarterly, no. 222 (2015): 403–29.

Wang, Zheng. “National Humiliation, History Education, and the Politics of Historical Memory: Patriotic Education Campaign in China.” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 4 (2008): 783–806.

Yip, Tiffany, and Andrew J. Fuligni. “Daily Variation in Ethnic Identity, Ethnic Behaviors, and Psychological Well-Being among American Adolescents of Chinese Descent.” Child Development 73, no. 5 (2002): 1557–72.

Zhou, Min, and Hanning Wang. “Anti-Japanese Sentiment among Chinese University Students: The Influence of Contemporary Nationalist Propaganda.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 46, no. 1 (April 1, 2017): 167–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261704600107.

I first encountered Dong Kingman’s work at the Cantor Art Center at Stanford University in September 2022